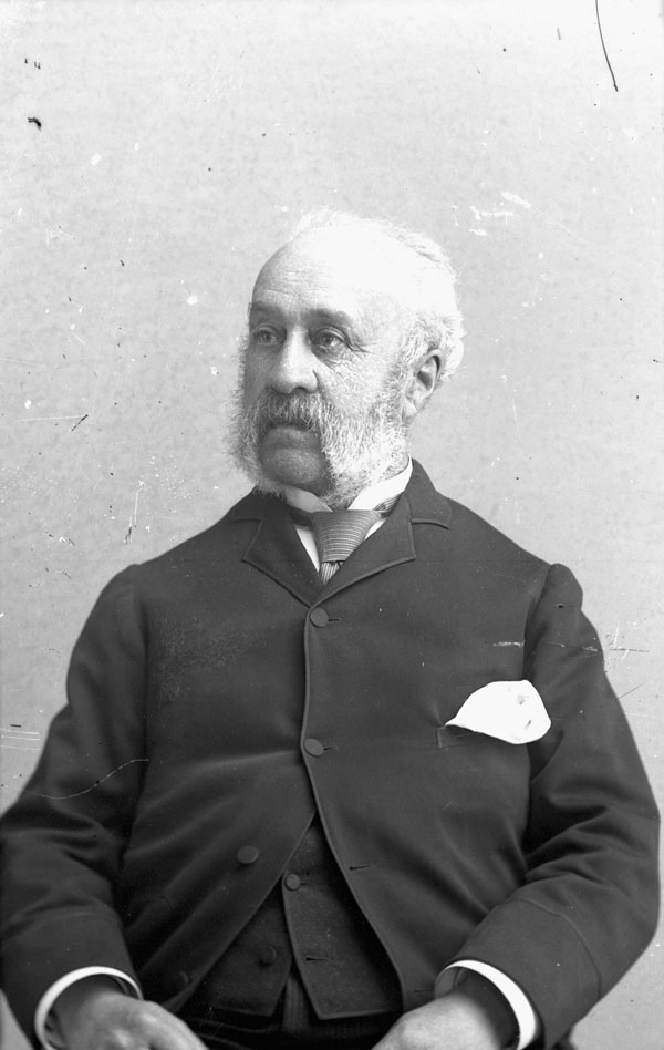

Great Canadian Architects since 1800: Thomas Fuller

On 6 June 2016, the architect Thomas Fuller was designated a

National Historic Person.

Is there one of his buildings near you?

If you're looking through the Canadian Register of Historic

Places (CRHP) the chances are that you're already interested in

Canada's built environment. You might be surprised how many

buildings on the CRHP database were designed by some of Canada's

greatest architects. One architect whose architectural designs and

prolific output proved influential in the field of Canadian

Architecture was Thomas Fuller, Chief Architect to the Department

of Public Works (DPW) 1881-1896 a period often referred to as the

golden age of federal architecture in Canada. Fuller's main

works are available on both the CRHP and the Dictionary of Architects in Canada where Robert

Hill has made his Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Canada

1800-1950 available online.

After 1867, the newly created Dominion Government was

responsible for creating and maintaining its own public buildings

and so a public works department was formed to take this in hand.

In 1871, the Engineering Branch of the DPW was enlarged to include

an Architect's Branch. This eventually became the Chief Architect's

Office. Thomas Seaton Scott (1826-95), the first Chief Dominion

Architect, was succeeded by Thomas Fuller (1823-98).

Fuller instilled a high level of

professionalism and the consistent production of high quality

buildings soon established the department`s position within the

Canadian federal bureaucracy. Already with an international

reputation, Fuller left England in 1857 to set up practice in

Toronto with Chilion Jones. With Fuller as designer their firm won

two important competitions, the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa in

1859, and the New York State Capitol in Albany in 1867.

Fuller instilled a high level of

professionalism and the consistent production of high quality

buildings soon established the department`s position within the

Canadian federal bureaucracy. Already with an international

reputation, Fuller left England in 1857 to set up practice in

Toronto with Chilion Jones. With Fuller as designer their firm won

two important competitions, the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa in

1859, and the New York State Capitol in Albany in 1867.

In 1881, Sir Hector-Louis Langevin, Minister of Public Works

appointed Fuller Dominion Chief Architect. Langevin wanted high

design standards and to create an imposing government presence

across the country. During Fuller`s tenure the department expanded,

increasing output to cope with events such as the opening of the

Prairies and other government initiatives. A small department in

1881, the Chief Architect's Branch soon grew producing a large,

innovative body of work. By the late 1880s, however, budgetary

cutbacks led to more economic designs and standardization.

Although responsible for buildings such as the

Langevin Block, an early, expensive project, Fuller's department

also excelled in the design of small to medium sized public

buildings tailored to individual sites, perhaps best seen in the

smaller individually designed post offices. Now cherished community

landmarks these picturesque structures, sometimes asymmetrically

designed, often feature a blend of Gothic and Romanesque details,

stone gables, and corner positioned clock towers.

Although responsible for buildings such as the

Langevin Block, an early, expensive project, Fuller's department

also excelled in the design of small to medium sized public

buildings tailored to individual sites, perhaps best seen in the

smaller individually designed post offices. Now cherished community

landmarks these picturesque structures, sometimes asymmetrically

designed, often feature a blend of Gothic and Romanesque details,

stone gables, and corner positioned clock towers.

Public Works had a huge impact on the built environment in

Canada. Chief Architect until 1896, Fuller's tenure witnessed the

construction of approximately 140 buildings nationwide, of these

approximately 78 were federal buildings and post offices. These

buildings created and consolidated a federal government presence

across Canada.

Changes in architectural styles in federal architecture are

reflective of stylistic changes in Canadian Architecture as a

whole. Fuller's work for the federal government reflected the

picturesque eclecticism of the period. This free and eclectic use

of Gothic, Romanesque, Flemish, British vernacular, and classical

elements is most apparent in his early buildings.

Fuller's period of tenure occurred at a time when the

architectural profession was becoming more developed, when new

materials, technologies and engineering methods were becoming

widely available, and when architects were creative

stylistically.

Under Fuller's  tenure the DPW delivered attractive,

well-designed buildings in a short time period and usually within

budget. His work is distinguished by its excellent site use,

contrasting surfaces, love of texture, attention to detail, and

good craftsmanship and materials. Under Fuller's direction the DPW

consolidated its facilities for in-house design and construction

supervision. The government of the day successfully extended its

federal presence through services to smaller communities. This

resulted in a series of well constructed post offices in towns and

cities across Canada.

tenure the DPW delivered attractive,

well-designed buildings in a short time period and usually within

budget. His work is distinguished by its excellent site use,

contrasting surfaces, love of texture, attention to detail, and

good craftsmanship and materials. Under Fuller's direction the DPW

consolidated its facilities for in-house design and construction

supervision. The government of the day successfully extended its

federal presence through services to smaller communities. This

resulted in a series of well constructed post offices in towns and

cities across Canada.

Thomas Fuller died in Ottawa in 1898 and is buried in Beechwood

Cemetery, which was designated a National Historic Site of Canada

in 2002.

In 2016, Thomas Fuller was designated a National Historic

Person.